Sake Guide

What is Sake?

-

By Natsuki Kikuya – Sake Samurai, WSET Sake Qualification Manager

-

After spending past 12 years introducing, teaching, and promoting sake here in UK, the public response to this drink has changed phenomenally. People use to back away when I brought free sake samplings at my first restaurant worked as a sake sommelier, and now I see so many are leaning towards to learn more about it with an even seen enthusiasm. However, when I say the word “sake”, majority of people in UK still think it is a kind of high proofed abv only served scorching hot.

-

Japanese restaurants have been meeting points for many to taste and experience sake, yet many have never chosen it to casually open for dinner with their daily non-Japanese home cooking.

If you trace the food culture and history of Japan, there is a unavoidable relations between our land, abundant source of water and rice production. Ever since the Japanese descendants had brought wet rice cultivation culture from China over 5,000 years ago, rice has always been the center of our diet and has been playing the essential role for the Japanese food culture. As a byproduct of rice, purely fermented alcohol drink from rice and water "sake" became a national alcoholic beverage of Japan since over 2,500 years ago.

Because It was firstly produced within the shrines of Japan's oldest religion Shinto, Sake still is a key element of many Shinto rituals and Japanese festivals. Sake is linked to Japanese culture in many ways and expresses the beauty of Japanese nature, traditions, culture and whole spirit.

It is often pronounced "SAH-ki" by English speakers, yet in Japanese it is more like "SAH-KEH". It literally means “alcohol” in general so if you want to specify this drink we call it “Nihonshu 日本酒” in Japan, which translates as “Japanese alcohol”.

Sake is gently fermented, and is in a family of beer and wine with an average of 15-16% abv. It can be enjoyed in the widest range of temperatures from chilled to warm or hot, depending on the style or flavor characteristics of sake.

From following articles, I would like to explore more details in ingredients, categories, tasting, paring, temperature and history of sake.

Ingredients

RICE 米

The reason why sake is historically related to Japanese Shinto religion comes from sake’s main ingredients; rice. Our diet has been nourished by the wet rice cultivation “Inasaku 稲作” culture since 2,500 years ago, and within Shinto religion, people believed the existence of “Inadama 稲魂”, that rice paddy has a soul and spirit. Therefore Rice and Sake has been the religion of Japan throughout the history.

There are two types of rice for sake making, table rice and “Shuzo-koteki-mai 酒造好適米”. Table rice is everyday rice that we eat as a meal. It contains more fat and protein, and does not have “Shinpaku 心白”, appearance of starch in the centre. Shuzo-koteki-mai is designed to meet the needs of making good quality sake and it has special features to be qualified.

1. Large in size (25-30g/ per 100 grain)

2. Starch in the centre is apparent (called as Shinpaku)

3. Minimum amounts of protein and fat

4. The grain has a high absorption level

5. Hard on the shell and soft inside (when it is steamed)

Rice production for sake only takes up 5% of whole rice production in Japan and within that number, it is only 1% of them are for Shuzo-koteki-mai. Since it is not easy to grow, it tends to be high in price. The king of sake rice, Yamada-nishiki 山田錦 from special A region, which is most expensive and has high quality, could cost about three times more than the regular Shuzo-koteki-mai does. Even though Shuzo-koteki-mai is an ideal choice, there are more breweries today using table rice to beautiful sake in lower price. Please check the name of rice used next time you encounter Sake!

WATER 仕込み水

Brewing sake takes enormous amounts of water. From washing and steaming rice, cleaning all the equipment as well as fermentation stage. It will normally require about 50 times the weight of the rice. Also, it makes up 80% of the entire ingredients, since the rice grain does not contain any juice. It is natural to say that the quality of the sake is influence a lot on the quality of the water.

As Japanese islands are surround by the oceans, Japan has an abundant access to the water from the mountain, river and ocean, and there are several areas well known for high quality water. Most sake brewery tends to locate in the best water source in each region. Rice is something you could buy from other area but the source of water is an asset from the nature.

Generally, water could be classified by hard water and soft water depends on significant quantity of dissolved minerals, such as calcium and magnesium. Both of them do have a potential to make good quality of sake but the most suitable water is believe to be “semi-hard water” known as Miyamizu宮水 of Nada region. Hard water is rich in minerals that fastens the fermentation, resulting dry and masculine sake. Soft water has less minerals and create slower & gentle fermentation, and this results softer and feminine style sake, known as “Fushimizu伏水” of Kyoto region. If you have any chance to visit Sake brewery, we highly recommend to try their “Shikomi-mizu 仕込み水”, the water of the berwery used for sake making. The quality of water tells stories itself how the flavour and texture of each sake was protected from generation to generation.

KOJI 麹

Koji-kin (麹菌), in scientific term Aspergillus Oryzae, is a type of mold spores that has been a foundation for the fermenting food culture of Japan for many years. It is a beneficial and safe variety of bacteria used for Miso, Shouyu (醤油, soy sauce), Sake, Mirin (味醂, sweet sake for cooking), rice vinegar, Shochu and various other ingredients in Japan.

Grape juice contains sugars, which ferment in the presence of yeast, but with beverages made from grains, such as sake and beer, it is first necessary to use enzymes to break down the starch in the grain to convert it to sugar before yeast fermentation. In beer brewing, malt is used as the source of these enzymes, but for making sake, Kome-Koji (米麹) is the key player. Kome-Koji is steamed rice inoculated with koji-kin, it creates enzymes that convert rice starch into sugar, which the kobo (酵母, yeast) feeds on. Koji also produces the other type of enzyme that breaks down protein and produces amino acid and peptide, which create unique characteristic of each sake.

Koji production is the heart of the sake-brewing process, and this process is most exercised, in the mind of master brewer. It requires constant control and adjustment of temperature throughout its 40 to 48 hours process in Koji-muro (麹室), a special temperature-controlled room and traditionally covered with cedar wood with electric heating wire or convection heater. (In modern settings more and more stainless-steel covered koji-muro can be seen.) The koji itself releases heat and koji temperature has to be checked every 2 hours in day and night.

YEAST 酵母

Yeast, Kobo 酵母 in Japanese plays a critical role in determining sake quality. Until the early twentieth century, sake was made using naturally occurring yeast. Over the decades, technologies improved and there were more and more practices of purely isolating and selecting yeast from the moromi (醪 main mash) of a brewery that had produced good sake. Many breweries have their own prosperity yeast strains which is discovered and exclusive to them.

Since 1906, yeast selected in this manner has been distributed largely and widely by the Brewing Society of Japan as Kyokai-kobo (協会酵母, Brewing Society yeast). Kyokai-kobo is numbered, and packed in ampules. Currently, the most widely used yeasts are Sake yeast kyokai #6, #7, #9, #10, and #14. Each produces its own aroma and taste characteristics and the specific choice depends on the desired sake quality. More recently, brewers have been utilizing microbial technology to produce yeasts designed to increase the amount of esters delivering a fruity aroma.

After 1990s, numerous yeast strains produced by several prefectures with advanced area of study had appeared in the market such as Shizuoka kobo, Yamagata Kobo, Akita Kobo and Fukushima Kobo. Even though using cultivated yeast such as Kyokai-kobo / regional yeasts are still majority, it is becoming slight trend by handful producers to go back in tradition to revive using ambient yeast or proprietary yeast (蔵付き酵母).

Categories & Label Terms

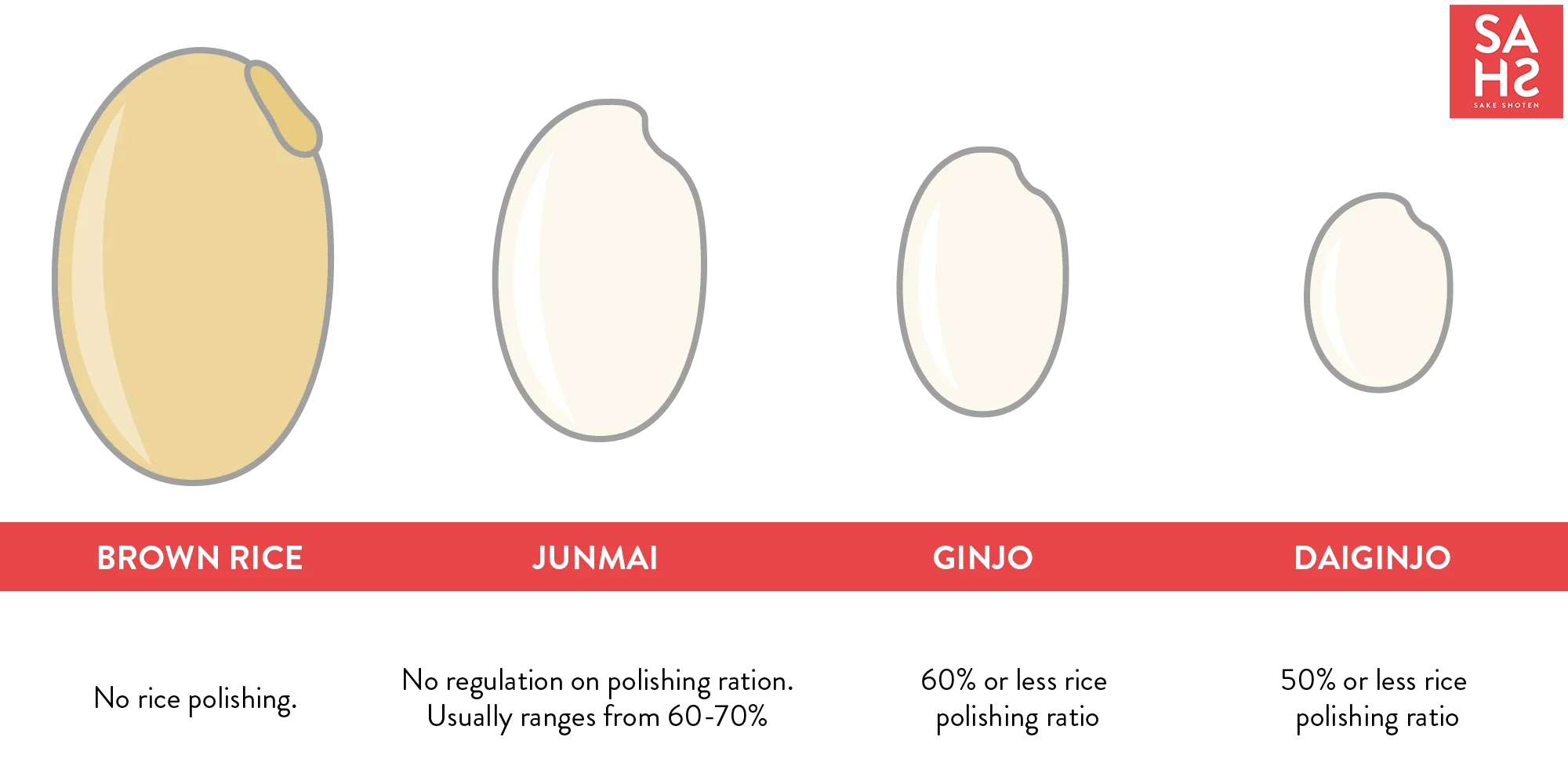

At beginning stage, harvested rice is polished (milled) down to certain size by removing outer layers. This process is essential to decide the category of sake and its style. As each grain of sake rice contains "Shinpaku / heart" of rice in the middle which is high starch concentration, the outer layers of impurities such as proteins, vitamins, fats and lipids would be removed by rice polishing, in order to make the sake purer and cleaner styles.

Here are some categories of Sake:

Collapsible content

FUTSU-SHU 普通酒

Translates as “regular sake”, which fits in outside of premium sake category, takes up 70% of market products. No minimum rice polishing requirement and higher addition of other ingredients such as brewer’s alcohol and amino acid.

HONJOZO 本醸造

This sake has a small amount of brewer’s distilled alcohol added at the final process. The rice polishing ratio has to be 61% to 70% at most. The addition of the alcohol makes the sake lighter umami and acidity, cleaner, crisper and drier styles, easy to accommodate the paring with different fish variety of sashimi & sushi. Can be enjoyed warm/hot and Try if you like mulled wine.

JUNMAI 純米

Junmai is translated to “pure rice” and made by only rice which is milled down to over 61% and no maximum limit of polishing ratio. This type of sake often has a rounder, fuller bodies and more complex styles, with more cereal or steamed rice driven notes and richer umami and acidity. Can be enjoyed warm/hot. Try this category if you like: Chardonnay or Pinot Noir

JUNMAI GINJO / JUNMAI DAIGINJO 純米吟醸 /純米大吟醸

Daiginjo stands for the sake made with rice milled down to at least 50% of its own original size, and Ginjo to be to between 51-60% remaining from original size. This type tends to be extremely elegant, pure and smooth, light to medium body, less umami and significantly aromatic. The flavours tend to have fruity characteristics such as fresh melons and green apples, pears, tropical fruits, and ripe banana. Anise seeds and floral fragrance is also typical "ginjo-aromas". Try this category if you like: Sauvignon Blanc or Viognier.

GINJO / DAIGINJO 吟醸 / 大吟醸

Ginjo is sake made with rice milled down to 51% to 60% of its own original size, and Daiginjo to at least 50% or below, and for this category a small amount of brewer’s distilled alcohol added at the final process. Brewer's distilled alcohol will extract the aromas of sake and make the final products more aromatic and spicier. This type also tends to be lighter, refresher, and pure styles. Try this category if you like: Chenin Blanc or Dry Riesling.

KOSHU 古酒

Long aged. Amino acid and sugar in sake creates Millard Reaction in sake to darker colours and caramelise the flavours. Typical Koshu has oxdative & rich flavor characters such as Sherry, with distinctive gold, amber and sometimes brown colours in glass. It is often enjoyed with salty and pungent dishes or as a digestive.

KIMOTO / YAMAHAI 生酛 / 山廃

Kimoto is the traditional method roots back to Edo periods over 300 years ago, and Yamahai is the simplified version invented about 100 year ago. These terms represent the method of sake fermentation starters using natural lactic acid bacteria in the air to create safe environment for the sake yeast to multiply. This process takes twice longer compared to conventional modern methods and also is much more labour intensive, yet some producers choose in respect for traditions and extra layers of flavours and creamy mouthfeel created by natural lactic acid bacteria. Even though sake made by this method accounts for less than ten per cent of sake produced, it is worth recognising as many people are big fans of these structured, rich sakes with deep flavours and great acidity. Even it is becoming slight trend these days, sake made with Kimoto and Yamahai methods only accounts for 5 percent or so.

BODAIMOTO / MIZUMOTO 菩提酛 / 水酛

Made with 500 year old monk’s method roots back in Shoryakuji temple in Nara Prefecture; oldest shubo method existing, it is revived by Tsuji Honten in Okayama and now only shobo made in the Shoryakuji temple can be called as Bodaimoto (apart from Tsujihonten who has the patent). Mizumoto is used for the shubo made in the same style outside of the area. Very rare and only handful of sake makers uses this method.

KIJOSHU 貴醸酒

Sweet style of sake made with replacing some water with sake on the third addition of Day 4 for main fermentation addition. Kijoshu is often has potential to mature, so many kijoshu are aged many years.

NIGORI にごり

Partially filtred sake. It is cloudy due to remaining rice sediment from coarse filtration. All sake has to be filtered and it is wrong translation to say unfiltered sake. Creamy, textuous and gently sweet, slight expression of rice, often be great with spicy dishes or for light dessert. Various levels of lees and category found in this style of sake. Very light cloudy sake is called Usu-nigori or Sasa-nigori.

MUROKA 無濾過

Non-charcoal fined. Even though most of the sake is going through charcoal fining after the main filtration in order to remove slight lemon-green colours (natural colours of freshly filtred sake is not water colour!) and unwanted bitter or astringent flavours. Yet some producers want to express everything uses low or no charcoal fining as it could remove the good flavours of sake. Muroka sake is often texturous and could be slightly coloured or hazy.

NAMA(ZAKE) 生酒

Unpasteurised. As filtred sake still contains lots of koji enzymes and could contain some bacteria to spoil the sake, most sake are pasteurised to stablise the quality. Some seasonal sake are sold unpasteurised to showcase the extreme freshness; Namazake is typically expressive, fresh and slightly nutty. You have to keep Namazake always in the fridge and consume quick (ideally within 10months after bottling). Some Nama is intentionally matured longer to express the caramel and toasted nuts characters as exceptions.

GENSHU 原酒

Undiluted. When filtred, most sake has 17-20% abv and producer adds little water to balance the flavor and alcohol. As an option producer can skip this process to express higher flavor intensity. Not all Genshu are high abv though; the trend these days are 14-15% abv Genshu sake.

TARUZAKE 樽酒

Cedar cask stored. Japanese cedar woods are often used to make, store and transport the sake in the past before glass / stainless containers are introduced to Japan. Taruzake is traditional style of sake which has spicy, pungent and aromatic woody notes of Japanese cedar. Most common occasion you see Taruzake would be barrel opening ceremony (Kagami-biraki in Japanese), where party hosts knows wooden lids with hammers and party guests enjoyed the sake stored in the cedar cask. As cedar woods have strong aromas, sake is only stored at short periods (10-14days) in casks.

TOKUBETSU JUNMAI / TOKUBETSU HONJOZO 特別純米/特別本醸造

Tokubetsu means “special”, so how special is Tokubestu Junmai or Tokubetsu Honjozo? There are several options for suing these label terms. It is either of 1) sake is made using rice polished ratio lower (meaning rice is more polished away) than average Junmai or Honjozo, which is normally around 61-70%. or 2) rice they use is special sake rice to notice, or 3) using special methods or techniques to make these categories special. It has to be legally recognized terms such as Kimoto, Yamahai, Taruzake, etc. Only Junmai and Honjozo categories get this “Tokubetsu” crown on top of their names. It is confusing terms for many people but it is used mostly for marketing purposes to offer something unique and special than everyday bottle of Junmai / Honjozo, yet not as floral / fruity as typical Ginjo style of sake.